The way in which the narrative of the early English Reformations is written has been a vital subject for historiography both early modern and modern. This article looks at the ways in which literary texts in the period c. 1549–1613 attempted to write the history of the Reformation within nascent forms of narrative Tragedy (dialogue, verse history, drama). Focusing on an Edwardian dialogue, a Marian poem and Shakespeare's and Fletcher's Henry VIII, the article looks at how these works attempted to make historical sense out of an era characterized by sudden political and religious reversals and upheavals, processes which themselves blighted the fate of these texts and their authors. In Bernadino Ochino's Tragoedie (1549) the rise of the papacy and its fall in sixteenth-century England is formed into a complex proto-Miltonic providential narrative. In William Forrest's History of Griselda II (1558), the Reformation is constructed as a sharply gendered masculine transgression drawn on the template of Chaucer's Clerk's Tale. Finally, in Shakespeare's and Fletcher's Jacobean history play, a vision of profound ambivalence is produced out of the various claims of religious triumph and literary tragedy.

De Casibus Tragedy Definition

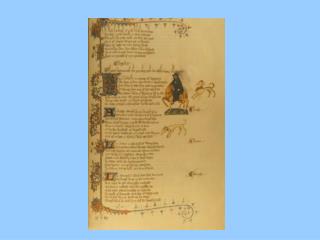

Fortuna. From John Lydgate, The hystorye sege and dystruccyon of Troy, London, 1513. By permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

The medieval concept of tragedy was quite different from that of classical literature. Tragedy was less the result of individual action than a reflection of the inevitable turning of Fortune's wheel.

De casibus tragedy had an ancient pedigree as well with Plutarch's Lives as a model that loomed large over the Renaissance generally and Shakespeare in particular. However, de casibus tragedy easily lent itself to Christian moralizing, and in Shakespeare's time, the conventional wisdom seemed to be that any work worth publishing was worth. To be related to tragedies (Tragedy and Comedy. In stricto sensu, Kelly is right that the prose of the e casibus does not. D emulate the high style of the genre, but I am persuaded by Zaccaria (p. Xlviii of the in-troduction to his edition) that there are substantial non-formal similarities worth keeping in mind.

In the illustration, Fortune, traditionally female because of the association of women with the moon and changeability, stands behind the wheel with outstretched wings. She continually moves the Wheel--on which at the top is a king, at the bottom a beggar.

- More on Renaissance conceptions of tragedy*,

- More about the philosophical roots of Medieval tragedy in Boethius*.

Sad stories. . .

Chaucer's monk, reacting against the assumption of the Host that he will tell a tale of action and love, relates a series of anecdotes about those who fell from happiness to misfortune at the moment they least expected it*.

Such stories are known as de casibus tragedies, after the work by Boccaccio, De Casibus Virorum Illustrium (Examples of Famous Men), which is a collection of moral stories of those who fell from the heights of happiness. Both Shakespeare and Marlowe* created characters aware of the de casibus tradition.

The way in which the narrative of the early English Reformations is written has been a vital subject for historiography both early modern and modern. This article looks at the ways in which literary texts in the period c. 1549–1613 attempted to write the history of the Reformation within nascent forms of narrative Tragedy (dialogue, verse history, drama). Focusing on an Edwardian dialogue, a Marian poem and Shakespeare's and Fletcher's Henry VIII, the article looks at how these works attempted to make historical sense out of an era characterized by sudden political and religious reversals and upheavals, processes which themselves blighted the fate of these texts and their authors. In Bernadino Ochino's Tragoedie (1549) the rise of the papacy and its fall in sixteenth-century England is formed into a complex proto-Miltonic providential narrative. In William Forrest's History of Griselda II (1558), the Reformation is constructed as a sharply gendered masculine transgression drawn on the template of Chaucer's Clerk's Tale. Finally, in Shakespeare's and Fletcher's Jacobean history play, a vision of profound ambivalence is produced out of the various claims of religious triumph and literary tragedy.

De Casibus Tragedy Definition

Fortuna. From John Lydgate, The hystorye sege and dystruccyon of Troy, London, 1513. By permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

The medieval concept of tragedy was quite different from that of classical literature. Tragedy was less the result of individual action than a reflection of the inevitable turning of Fortune's wheel.

De casibus tragedy had an ancient pedigree as well with Plutarch's Lives as a model that loomed large over the Renaissance generally and Shakespeare in particular. However, de casibus tragedy easily lent itself to Christian moralizing, and in Shakespeare's time, the conventional wisdom seemed to be that any work worth publishing was worth. To be related to tragedies (Tragedy and Comedy. In stricto sensu, Kelly is right that the prose of the e casibus does not. D emulate the high style of the genre, but I am persuaded by Zaccaria (p. Xlviii of the in-troduction to his edition) that there are substantial non-formal similarities worth keeping in mind.

In the illustration, Fortune, traditionally female because of the association of women with the moon and changeability, stands behind the wheel with outstretched wings. She continually moves the Wheel--on which at the top is a king, at the bottom a beggar.

- More on Renaissance conceptions of tragedy*,

- More about the philosophical roots of Medieval tragedy in Boethius*.

Sad stories. . .

Chaucer's monk, reacting against the assumption of the Host that he will tell a tale of action and love, relates a series of anecdotes about those who fell from happiness to misfortune at the moment they least expected it*.

Such stories are known as de casibus tragedies, after the work by Boccaccio, De Casibus Virorum Illustrium (Examples of Famous Men), which is a collection of moral stories of those who fell from the heights of happiness. Both Shakespeare and Marlowe* created characters aware of the de casibus tradition.

On his return from Ireland, Shakespeare's Richard II likens himself to one of those whom Fortune has punished. (Click for more*.)

De Casibus Tragedy Meaning

Footnotes

De Casibus Tragedy

Lydgate and The fall of Princes

John Lydgate, writing a generation after Chaucer, wrote a long poem, The Fall of Princes, in the same tradition. It is a translation of a French work, which itself is based on Boccaccio.

A Marlovian hero falls

Marlowe's tragedy of Edward II has a character, Mortimer, who mounts to great power as Edward falls. At the end of the play, Edward's son, Edward III, takes over, and has Mortimer executed for the death of his father. Mortimer, in a manner typical of Marlowe's heroes, dies defiantly:

Base Fortune, now I see, that in thy wheel

There is a point, to which when men aspire,

They tumble headlong down: that point I touched,

And, seeing there was no place to mount up higher,

Why should I grieve at my declining fall?

(5.6.59-63). . . Of the death of kings

For God's sake let us sit upon the ground

And tell sad stories of the death of kings:

How some have been deposed, some slain in war,

Some haunted by the ghosts they have deposed,

Some poisoned by their wives, some sleeping killed,

All murdered.

(Richard II, 3.2.155-160)A medieval historian, Adam of Usk, also described the fate of Richard II as a tragedy of fortune:

Though well endowed as Solomon, though fair as Absalom, . . . yet . . . didst thou in the midst of thy glory, as Fortune turned her wheel, fall most miserably into the hands of Duke Henry, amid the curses of thy people.

Lessons in tragedy

In medieval works, the tragedy of those who fell was often less the result of any failing in their lives or actions than the result of the capriciousness of Fortune. But by the Renaissance, the moral effectiveness of pointing out the dire result of vice and sin meant that the protagonists were more often shown to be responsible for their falls.

The best, and most popular example of the genre in the renaissance is A Mirror for Magistrates, Wherein may be seen by example of others, with how grievous plagues vices are punished; and how frail and unstable worldly prosperity is found, even of those whom Fortune seemeth most highly to favour. The Mirror was published in 1559, and many times after.

Boethius' Consolation

The Consolations of Philosophy, written by the sixth century statesman and philosopher Boethius, was a profoundly influential work, translated by Chaucer, and used as the philosophical basis of one of Boccaccio's most read works, De Casibus Virorum Illustrium (Stories of Famous Men), where the lives of those whose fortune changed abruptly from success to failure or death are told.

Boethius argued that the turns of Fortune's Wheel are both inevitable and providential--that is, even the most coincidental of events is actually part of God's plan. Thus the character of the individual is no more important in deciding fate than the influence of the stars, since both are agents of God's will.

Boccaccio

A contemporary of Petrarch, Boccaccio's importance to Shakespeare was in the stories from the Decameron which he used in a number of his plays. In each case, however, he could have found the story in an English version.